‘Break it down’ is not just a great suggestion put forward by Tone-Loc in his misogynistic yet beguiling 80’s rap classic ‘Funky Cold Medina‘.

It would be remiss to overlook the title of the text: it is deceptive in its simplicity but it draws us to key ideas in this text. This novel features two rivers: the broad, bustling Thames which is the lifeblood of the city of London and the quiet, meandering Hawkesbury which reveals a little of the landscape at every turn.

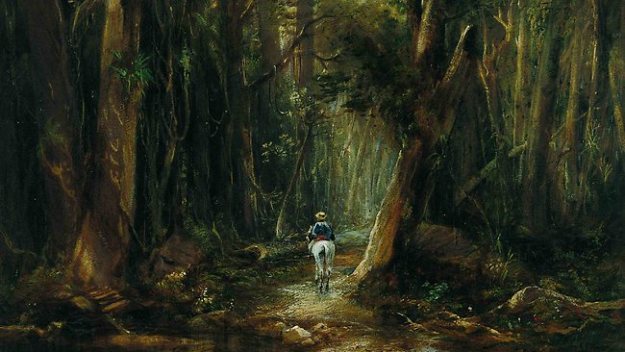

The river revealed itself, teasingly, never more than a bend at a time, calm between its walls of rock and bush. As the Queen rounded one high spur of land, another camein from the other side, so they interlocked as neatly as gear-wheels. Once reach resembled all the others: cliffs, a fringe of glossy green mangroves, green water. Even the skyline gave no clues, each bulge of high land like the others, striped with shadows from clouds passing in front of the sun.

The wind was flukey, bringing with it a dry sweet clean fragrance. The boat was drawn up by the tide as if pulled by a string, lowly, calmly, curve after curve. The twists of the landscape closed in behind them. It was not possible to know where they were going, or to see where they had been.

The Secret River, p.102

Thornhill’s story is one of a series of revelations and secrets. Consider what is known and unknown to Thornhill, both about the land, its inhabitants and about himself. What he chooses to share and what he chooses to keep private are important in this text and the title reminds us that we should be looking for how secrets operate.

Sal tightened her shoulders into herself and leaned towards the fire, not looking at her husband. They had never disagreed on anything that mattered. He wished he could explain to her the marvel of that land, the way the sunlight fell so sweet along the grass.

But she should not imagine it, did not want to. He saw that her dreams had stayed small and cautious, being of nothing grander than the London they had left. Perhaps it was because she had not felt the rope around her neck. That changed a man forever.

The Secret River, page 100

Thornhill makes conscious and strategic decisions to keep secrets. Is his motivation love or self interest or something else altogether?

He would tell her about the fish, even bring her up to see it. But not yet. She was content enough in her little round of flattened earth: what was the good of showing her the other world beyond it?

The thing about having things unspoken between two people, he was beginning to see, was that when you had set your foot along that path it was easier to go on than to go back.

The Secret River, p.155

Consider too, the secrets of the indigenous population. Contrast their ways of knowing and the ways of interpreting a relationship with the land to the Europeans. Thornhill cannot conceive of another way of knowing and the failure of the communication is clear when he speaks to the elder. Aboriginal knowledge and understanding remain a mystery to him.

When he spoke again it cut across Thornhill’s humour like water on a flame. He made a chopping action with the side of his hand, pointing to the square of dug-up dirt and the daisies wilting in a heap. This time his voice was not so much a running stream. It was more like stones rolling down a hill.

Thornhill gestured at the cliffs, the river glinting between the trees. My place now, he said. You got all the rest. He drew a square on the air with his arms, demonstrating where his hundred acres began and ended….The man was not impressed. He did not look around to follow the sweep of Thornhill’s arm. He knew what was there.

The Secret River, p.144

THINK:

- How important is the river to the inhabitants of the region?

- What does a river represent to Thornhill?

- Which secrets does the river reveal to Thornhill?

- What secrets does Thornhill keep to himself?

- Try to draw some conclusions about the nature of secrets: what kind of secrets does the text suggest we have? How do we acquire them? Why do humans keep or share them? In what circumstances do we keep or share secrets? What does this tell us about human nature?

WRITE:

- Consider how secrecy will feature in your own writing. What a character might say out loud, their facial expressions and body language might not match. This can give some clue to your reader as to what they might be keeping private.

- Write her own thoughts and impressions of Thornhill’s motives and actions. How good might he be at keeping secrets? Sal is arguably a strategic thinker and a reasonable judge of character. You might consider her to be more shrewd than Thornhill realises. Perhaps Sal can see through the facade…

- Do not neglect the location in your writing. Describe the river to set the backdrop of your action or to enhance the mood of your text.